Henry B. Walthall: Biography--The D.W. Griffith Years

A Tribute Page to the Silent Film Star

The D.W. Griffith Years

D.W. Griffith (far left with hat, of course) with some of

his players. Walthall

center in dark coat (Thanks Hulda!).

Note: I spent a lot of time

and care writing this biography and tried to reference every source

I used so, if any visitor finds a use for any

of the information here or on the other pages of this

site, please note this source. Thank you, M.W.

One summer day in 1909, Henry B. Walthall left the Player's Club in New York

to find his friend James Kirkwood at the request of a producer. He was met at the

Kirkwood residence by Mrs. Kirkwood who told him her

husband was working in films. Walthall was shocked

at this news as motion pictures were not considered

a noble line of work in those days. "I can't tell you

how I felt," Walthall recalled, "An actor of the legitimate descending to

the pictures was beyond me. I told my friend's wife

as much. She smiled and said her husband was very

enthusiastic. Wouldn't I wait for him? I waited, and

when he came home, I saw a man aflush with a new idea

in which he took delight. He bubbled about pictures, and

I caught a glimpse of what he felt, altho (sic)

I still felt sorry for him" (Ames, pg. 140).

With James Kirkwood in Walthall's first

motion picture,

A Convict's Sacrifice, released

July 26, 1909.

The next day, out of curiosity, Walthall went to the Biograph studio with Kirkwood.

There he met the legendary director

D.W. Griffith. Being the type of actor he was looking

for, Griffith asked Walthall to be in the film with

Kirkwood. Reluctantly, Walthall agreed. Part of the

role turned into a practical joke. Walthall's character

was to dig a ditch until a girl playing his daughter

comes with a dinner pail and asks him to share his meal

with an ex-convict who is passing through (played by Kirkwood). Eyes on his work,

Walthall continued to dig the ditch for some time until, exhausted,

he demanded to know when the girl was to arrive with

the dinner pail. Griffith responded, "Not much longer,

just until you dig to that stone there. I promised the

contractor that if he would let us use this ditch you

would extend it three feet" (Katchmer). Walthall finished

his role in A Convict's Sacrifice and was offered

a salaried position as a player in the Biograph company.

It paid the same as his theatre work without the

traveling expenses. Still, Walthall was not sold on

the motion picture career and set off for England

with Miller's company in another run of The Great Divide.

The play was not the success it was expected to be and Walthall

returned to New York finding Griffith's offer still open.

This time, Walthall accepted. As Walthall recalled in 1934,

"With the exception of a year in vaudeville and a year

on the stage, I have been in pictures continuously ever

since 1909. If I'm lucky, I'll be in them until I drop" (Hill, pg. 56).

The stage actor definitely changed his attitude on the potential of film

as a career since the day he hoped to "rescue" his friend

James Kirkwood from the ignominious profession. "I have found

a new medium of expression with the same general lines as

the drama has, but with something else that is its own,"

admitted Walthall in 1916. "There is art, a great deal of

art, in pictures" (Ames, pg. 140).

In D.W. Griffith, Walthall found the premiere artist

of this "new medium" to guide him. Soon, he

would be in scores of Griffith shorts, developing the

emotional, yet restrained style of acting that would make

him one of the most popular stars of the silent screen.

Stardom, however, was not to be expected in the early days

of film. As Walthall remembered, "The films were a true

democracy then. Everyone, extra, characterman, leading lady

was paid the same [$5 a day in 1909]. There were

no stars. One day a man played the hero, the next day

he was shaking his fist in the mob, a girl was sometimes

the mistress and sometimes the maid" (Donnell, pg. 40).

Moreover, the actors did not receive the credit of

even having their names on the screen. "There wasn't

much incentive to our picture acting, for our names were

not mentioned in the casts," Walthall

reminisced in 1931. "We all bore numbers or fictitious names

given us by the public...The producers simply

wouldn't let us have that publicity. They were afraid

we would ask for more money and that the other companies

would steal us away from them. If anybody wrote in

asking who a certain player in a picture was, the only

answer the ardent fan would get was a number!" (Kingsley, pg. 76).

From the Biograph Bulletin for The Sealed Room,

released September 2, 1909.

One benefit to this democratic atmosphere was a special camaraderie

exhibited by the actors on the set. Speaking

of the good ol' days in a 1925 interview Walthall

sighed, "The studios were pleasant places and players

were personal friends, while now--the caste system

prevails. The leads do not speak to the lesser players,

those who have 'bits' do not speak to the extras" (Donnell, pg. 41).

Walthall was one of the more popular players in the Biograph

company, known affectionately as 'Wally.' D.W. Griffith's first wife, in her book

When the Movies Were Young, described 'Wally'

rendering old southern ditties for his fellow actors

and preparing a famous fried chicken luncheon (pp. 124, 177).

Of his progression as an actor, Mrs. Griffith maintained

that "'The Sealed Room' was the name of the screened emotion

that put Mr. Walthall over in the movies. Wally's

acting proved to be the most convincing of its type so

far. He was very handsome in his silk and velvet, and

gold trappings, with bejeweled chain around his neck, and the

most adorable little mustache" (pg. 112). The best

was yet to come for 'Wally.'

As an indian alongside Mary Pickford

in Ramona,

released May 23, 1910.

The Biograph crew left New York for California

to take advantage of the abundant sunlight. Soon after,

Walthall starred in the first two-reeler entitled

Ramona which was also the first motion picture version of a novel.

Running a full thirty minutes, double what most shorts ran

at the time, Ramona was greeted with much

enthusiasm from the Biograph company (Kingsley, pg. 77).

Future parts for Walthall would be even bigger, especially in 1914.

The four-reeler Gangsters of New York received

much publicity in the movie fan magazines of that year

(i.e. "Chats with the Players," Motion Picture Magazine,

April 1914).

A 1914 issue of Reel Life (actors earning their

public recognition the year before) pictured Walthall

four times for his roles in The Mysterious Shot

(directed by fellow actor Donald Crisp)

and The Floor Above (directed by old pal Kirkwood).

These films did not even represent Walthall's most memorable

roles of 1914. The Griffith classics Judith of

Bethulia (the last film for the Biograph company),

Home, Sweet Home, and The Avenging Conscience

made Henry B. Walthall a star.

With Estelle Coffin in the James

Kirkwood directed

The Floor Above.

John Howard Payne setting out to make a name for himself.

In Home, Sweet Home, Walthall played John Howard

Payne, whose famous song of the same name as the film's title

is shown to have helped so many lives as to atone for

the songwriter's own sins. Coincidentally, young Henry

played this song as his closer in his serenades in Alabama (Williamson, pg. 87).

Holofernes, the evil warrior in Judith of Bethulia,

was a role Walthall, himself, did not think he could play.

The reason was a familiar one to 'Wally.'

Perhaps the main cause for Walthall's lack of success

on the stage was his height. In 1929 the actor lamented, "I

never got very far in the theatre. Stock companies and touring

companies were my limit. I was with one show--'Under Southern

Skies'--for four years. My greatest stage disappointment

came from my size. Can you imagine what it is to rehearse

a part and know that you are doing well, and then to have

someone say: 'Your work is all that could be desired,

and we would keep you in this--if you were only an inch

or two taller!'" (Hayden). But Walthall's diminutive

stature was never an issue for Griffith. Walthall recalled,

"I hadn't expected to play Holofernes because I wasn't the

type physically. I stayed away from the studio, but

Griffith sent for me. I said, 'I can't play the part; I'm

too much of a shrimp.' But he had tried out a lot of actors,

and finally decided that I could do the part to suit

him better than anybody else could. So he found a way,

just as he always did. He put me on a pedestal and put

brass armor on me. I looked like a giant. I stayed up

there either on my throne or on a couch all the time. I

had two broadswords, and I threw those broadswords around

like a giant. The only other time you saw me I was riding

in a chariot across the battlefield and, of course,

that made me look tall. No, Griffith never said to me, 'You're too

small!'" (Kingsley, pg. 102). So, the 5'6 135 pound

actor played the mighty Holofernes, projecting "the

austere and commanding presence of a warrior" (Singer, pg. 56).

The Avenging Conscience in collage form.

Then came The Avenging Conscience which provided

the format for one of Walthall's

most celebrated performances and may, alone, have earned him the

title of "Edwin Booth of the Screen." Several articles, one as late as

1997, attest to its greatness. Based loosely on Edgar

Allan Poe's "A Tell-Tale Heart" and "Annabel Lee," Walthall's character,

angry that his sweetheart is not accepted by his uncle,

dreams of strangling his uncle to death and stuffing the

body behind a wall. While being questioned by

authorities, the noises he hears and the visions he sees

cause him to lose his grip on reality. In a 1916 article,

one admirer wrote, "His [Walthall's] great performance

was, to my mind, in "The Avenging Conscience"--a marvel

of character-drawing and of the dragging forth of the

innermost emotions. In this Walthall was almost uncanny,

and every movement of the man--the twitch of the lips, the

eloquent changes of the eyes, the hands, even the feet--was caught

by the audiences with painful reality" (Willis, pg. 56).

Eighty-one years later, Richard Schickel chose The Avenging

Conscience as the film to illustrate Walthall's acting

expertise. Schickel explains Walthall's mastery in the

interrogation scene: "Walthall (and the audience) sees visions which he

reacts to, but cannot overreact to, since it would signal to the

detective that he is on the right track and should continue

harassing this strange young man. Slowly, Walthall

comes apart psychologically; a medium close-up of his

oddly smiling yet troubled face, in conversation with himself,

reveals that he has inevitably lost control. A lesser

actor might have gone for a more demonstrative or affected

style of performance; Walthall is genuinely terrifying--

as he is terrified--because he is restrained and works with the power

of films' visual capacity to represent (un)reality" (pg. 57).

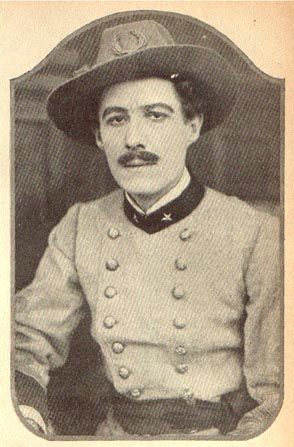

As memorable as this role was, the pinnacle of Walthall's

success came when D.W. Griffith selected him to play the lead

in his upcoming masterpiece, The Birth of a Nation.

As with Holofernes in Judith of Bethulia, Walthall

did not believe he was physically suited for the role

of Col. Ben Cameron. Walthall preferred to play Governor

Stoneman, a part that made up much of the play's version.

Griffith, however, believed Walthall, with his subtle

yet powerful body language and angry, expressive eyes, was

perfect for the role and the director would make Ben Cameron

"the outstanding part in the picture" (Kingsley, pg. 102).

In addition, Walthall's expert knowledge of Civil War

history and his prowess as a horseback rider convinced Griffith

to make his leading actor an assistant director to oversee

some of the battle scenes.

Several sources explain that, due to "illness," Walthall

was almost unable to undertake his famous role; one

source going so far as to claim that Walthall was

"not expected to live" (Rankin, pg. 96). The 6'3

Wallace Reid was on call just in case his services

as the not-so-little colonel were needed. This "illness"

is never given a name. Some mysterious "illness" also,

according to period magazine clippings,

sidelined Walthall from work a few times in his later

life. Perhaps repercussions from the malarial fever he

suffered while in the Army are to blame or possibly the

illnesses were more self-imposed. Several firsthand accounts show that

Walthall had at least some issues with alcohol, sometimes disappearing from the studio

for days at a time. Lillian Gish in The Movies,

Mr. Griffith, and Me explained that a bodyguard

was assigned to 'Wally' to assure he arrived at work on time

and did not imbibe excessively. Once, he gave his bodyguard

the slip and was found later napping in his hotel room (pg. 135). Such shenanigans

are disheartening, especially considering that Walthall

was 36 years old at the time. The story may help explain

the many references to some unnamed "illness" that

often creeps up in articles on Walthall. This information

also demonstrates just how great an acting talent Walthall was

considering that the legendary director put up with

such anxiety in order to have Walthall play the lead in his

greatest film.

Click here for the exciting

conclusion (well, not too exciting).

Please see the Bibliography

pages for details on the references used in this biography.

Free Website Counter