Henry B. Walthall: Biography--Escaping "Poverty

Row"

A Tribute Page to the Silent Film Star

Escaping "Poverty Row"

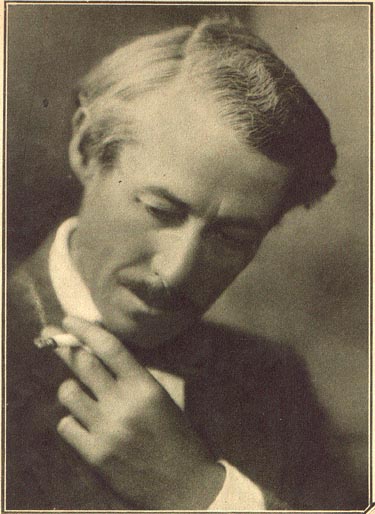

Cigarette card, circa 1916.

Note: I spent a lot of time

and care writing this biography and tried to reference every source

I used so, if any visitor finds a use for any

of the information here or on the other pages of this

site, please note this source. Thank you, M.W.

While The Birth of a

Nation assured Henry B. Walthall's place in motion picture history,

it did not assure that he would be on top of the film acting world

through the rest of his career. From 1914 to 1916, however,

Walthall was as popular, if not more so, than any other

player on the silent screen. On the

back of a period cigarette card (circa 1916) is stated that "Mr.

Walthall is probably seen in more pictures and places than any other

screen artist [and] is considered by many the best actor in the

motion picture world to-day." Fan magazines of the time

sport similar praises. One is shocked to see Walthall

ranked a lowly 19th in the 1916 article "The Twenty Greatest of Filmdom"

(Grau, pg. 181). Perhaps a readers' poll in the same

issue is more indicative of Walthall's popularity at

the time. He ranked a close #2 (19,760 votes to

Earle Williams' 19,920) for his role in The Birth of a

Nation as well as being listed four additional

times for other parts, including over 14,000 votes each

for his performances in Ghosts (#18) and The Avenging

Conscience (#7)

(pp. 179-80). At the zenith of his work under D.W. Griffith,

Walthall earned the princely sum of $175 per week (Katchmer). The

profession he once derided had made him a very wealthy and

famous man.

Walthall left Griffith following The Birth of a Nation.

Several reasons are given for his departure: uncertain

health caused the actor to stay in California rather

than follow the director back to New York (Rankin, pg 96),

he wanted to strike out on his own (Franklin, pg. 241),

or he was encouraged to leave because no obvious role

was available to him in Griffith's next big budget film,

Intolerance (Slide II, pg. 402). Whatever the reason

or reasons, Walthall's decision to leave Griffith had

an adverse effect on his career. As one author observed,

"His career, which undoubtedly would have developed along the

spectacular lines of those of Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh,

and Richard Barthelmess, came to a sudden standstill,

and he wasted a decade in interesting but minor films

quite unworthy of him" (Franklin, pg. 241).

Walthall starred in a few more classics in 1915. The

horror film Ghosts gave the actor a chance to top

the physical/psychological breakdown scenes of The Avenging

Conscience as a man who inherited his father's

debilitating disease. In the late spring of the same year,

Walthall joined the declining Chicago-based Essanay company (Slide II,

pg. 402).

His best portrayal for Essanay was that of Edgar Allan

Poe in The Raven. An ardent reader of Poe's works

since childhood, Walthall played the troubled soul more

convincingly than probably any other actor could. The following

year, Walthall starred or co-starred in several films

that received much attention including The Sting of

Victory, The Truant Soul, and the serial

The Strange Case of Mary Page.

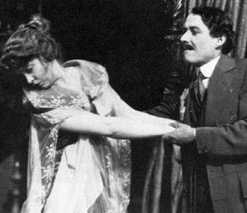

As Edgar Allan Poe in Essanay's The Raven.

The years 1917 and 1918 were pivotal for Henry B. Walthall,

both professionally and personally. After a two-year

stint in Chicago with Essanay, Walthall vowed to move

away from the bizarre, morbid roles that made him famous beyond

the "Little Colonel." "Never again!," Walthall asserted

to an interviewer in 1917, "If I can make a living

otherwise, I will never play a dope fiend again, or a booze fighter,

or a man with a portable soul. I'm off that stuff for

life, if I may be allowed to revert to a very expressive

slang phrase. I suppose it was all right in the

beginning. It was something new and different from the

sort of screen pabulum that was provided in those

early days...Perhaps it was the great war with its

attendant sorrows that brought about the changes in the

attitude of the screen patrons [Walthall's brother, Junius,

was wounded in the war] or, maybe they just

naturally sickened of grief and morbidity as a steady

diet. At any rate the ban is on that form of drama and

I hope for good" (Cohn, pg. 32).

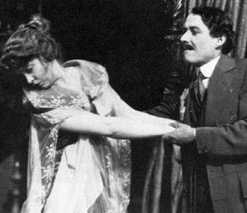

In His Robe of Honor.

Along with this change

in attitude regarding future character portrayals

came, in 1918, a change in companies.

Walthall started his own company Henry B. Walthall

Pictures Inc. under the aegis of Paralta Plays, Inc.

(Walraven). His Robe of Honor and Humdrum

Brown resulted

from this independent undertaking. Walthall had the

leading roles in both films under the direction of

Rex Ingram; however, neither film met much success.

That same year, Walthall found himself reuniting briefly

with D.W. Griffith in the forgotten film The Great Love,

co-starring Lillian Gish. Critics did not receive the

film well and faulted Walthall's acting as

"over-melodramatic" which, according to Anthony Slide,

"is possibly the reason Griffith decided not to use

him again until the coming of sound" (Wagenknecht and

Slide, pg. 101). Since the film is "lost," one cannot

see for one's self whether the critics were fair

in their assessment.

Being "over-melodramatic" in The Great Love.

Lillian

Gish is the victim.

Privately, Walthall also made a couple of life-changing

decisions between 1917 and 1918. While in Chicago,

he filed for divorce from his first wife of ten years, Isabelle

Fenton, on the ground of desertion. Fenton was an actress

of the stage who probably never ventured into film. No additional information on

this woman can be found. A clipping from an unknown

movie magazine states that the couple had been estranged

since March 1917. Accounts of his life with the Biograph

company include no mention of a wife. Certainly she would have

accompanied him at least on several occasions. One

may speculate that this estrangement first occurred

years before, perhaps when young Henry was a struggling

stage actor; however, documented hints as to the couple's

relationship are yet to be found. What is certain is

that, soon after the divorce, Walthall married Irish

actress Mary Charleson. They appeared together in several

productions before Mrs. Walthall gave up her acting career

to support that of her husband. The Walthalls' first

and only child, daughter Patricia, was born in 1918.

By all accounts, their marriage was a happy

one. Mary took active charge of Henry's business and personal affairs,

giving the actor more time to concentrate on his craft

(McGaffey, pg. 33). Henry also rehearsed his lines with Mary and she

often accompanied him on movie sets. One admirer of the couple commented,

"It does one good, in these hectic days of the 18th

Amendment [the dreaded Prohibition, of course!],

knee-length skirts [was the complaint that they were

too high, or not high enough?], suffrage, national

politics, and the usual 'cussedness' of the century, to

meet two people who are as sane, as wholesome and as

well-balanced as Mr. and Mrs. Walthall" (Gaddis, pg. 39).

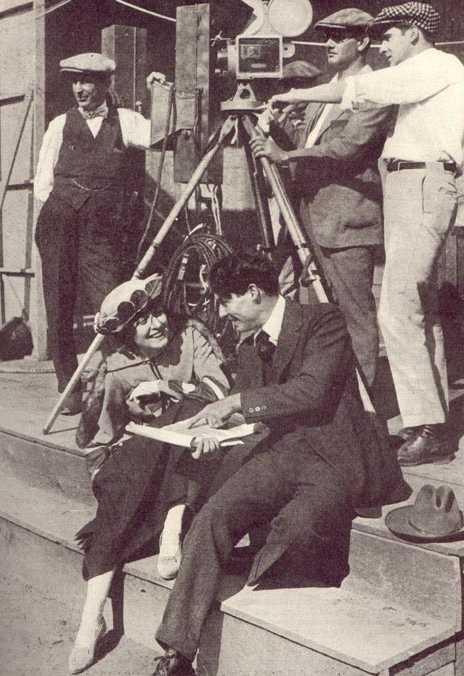

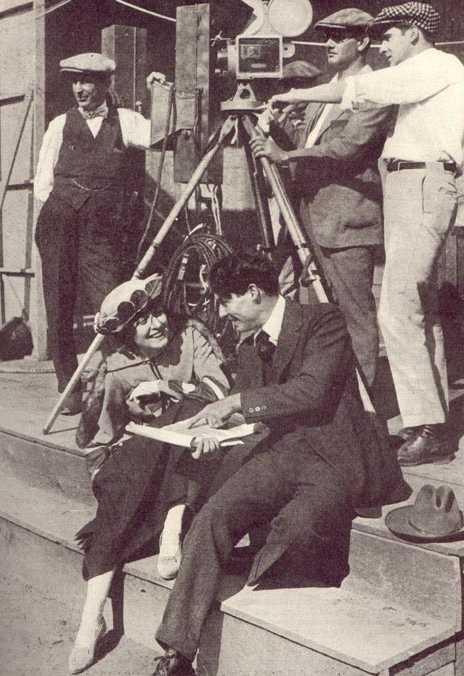

A "wholesome couple": Mary Charleson and

Henry Walthall going over

a script.

While Walthall's family life seemed to be stable, his

career was in rapid decline as the motion picture

world prepared to enter the "Roaring Twenties." Walthall

had two leading roles in suspense-filled dramas at the turn of the

decade in

The False Faces (1919) and The Confession

(1920). In the former, Walthall played Michael Lanyard, "The

Lone Wolf" from the Louis Joseph Vance pulp fiction

novels; in the latter, Walthall played one of those dreaded

men of the cloth who sets out to save his brother from the

gallows without revealing the confidentiality of the

real killer's confessional. After these, roles of

distinction were few and

far between. Important films in which he had bit parts

during the 1920s include Clara Bow's The Plastic

Age (1925) and Wings (1927), the latter

of which won the first Academy Award. Notable

films in which he had larger roles include One Clear Call

(1922), The Barrier (1926) with Lionel Barrymore,

The Unknown Soldier (1926), a reunion with

Lillian Gish in The Scarlet Letter (1926), and

the Lon Chaney films The Road to Mandalay (1926)

and the "lost" London After Midnight (1927), the

latter achieving cult status due to Chaney's over-the-top

vampire stills. Such production seems impressive; however,

it was still a far cry from 'Wally's' days with D.W. Griffith.

With Lon Chaney in the "lost" cult classic London After Midnight.

The movie magazines picked up on this dry period of

Walthall's career. In a 1926 issue of Motion Picture,

Walthall is pictured among others like Francis X. Bushman

in the article "Poverty Row": "It's a strange place, Poverty Row--gray

with disappointment and bitter with failure, yet shot through with

the golden gleam of hope. Work, work, work! Those going

up work eagerly. The Will o' Wisp, ahead,

beckons. Those, coming down, work doggedly, for bread--or

gaily, for bravado--or sullenly, for shame--and those

who are climbing up a second time, work silently. It

is harder the second time, because in failure, they are

burdened with the memory of success." Still, on the

"mythical ladder in Poverty Row," Walthall was an actor

who was "climbing up again" (Benthall, pp. 26, 113).

As late as 1932, Walthall is again pictured among others

of various occupations who have seen declining fame.

This time the word for it was "Fade-out;" in Walthall's

case, fading from "star to extra" (Parton, pg. 18).

Although, Walthall's star was fading, he still had the

magic to capture the imagination of 12-year-old John Griggs.

After seeing The Confession, Griggs began a

life-long devotion to the actor who "worked his sorcery

as he played a Catholic priest" (pg. 118). In 1922, Griggs

saw Walthall playing a dual vaudeville stage role as a French father

who believed his son had fled the French Army in an

act of unforgivable cowardice and then, later, as the

spirit of the Unknown Soldier--his son. Griggs admitted

that "following Walthall in the 'twenties was difficult" (pg. 119).

The young fan, who was also an aspiring actor, undertook treks

to out-of-the-way theatres to watch the master in bit

roles. Once Griggs was so distraught after seeing that

Walthall's part in DeMille's Golden Bed made up

only a few seconds that the operator cut him a few inches

of the scene (pg. 119). Later, Griggs collected 35 mm

prints and, in the 1940s, played The Confession

to an audience of teenagers at a local Catholic school.

According to Griggs, "after the show, when we collected

our six hundred questionnaires, not one teenager

had noticed the infirmities of this old silent picture.

One teenager wrote: 'I have never seen a silent picture

or heard of Henry B. Walthall but I'll never forget

his face'" (pg. 121). One shudders to think what the

reaction of today's teenagers would be.

A 1928 premiere for a starring theatre performance (his first in eight years)

showed that Walthall could still pack them in. D. W. Griffith was master of

ceremonies at the Grand Avenue Playhouse in Los Angeles for the premiere of

the play Speakeasy (also to be an early talking motion picture). The entire

theatre was decorated in Walthall's honor and the reservation list included such

names as Pola Negri, Alan Hale, Lon Chaney, Greta Garbo, Mary Philbin, Harry

Langdon, Edmond Lowe, Mack Swain, and Charles Chaplin (Los Angeles Record, March

19, 1928).

To most people outside the movie business who remembered him, however,

Walthall was still the

"Little Colonel."

Featured interviews with the actor

during this dry spell usually consisted of him going

down memory lane (15-20 years down it anyway, which

must have seemed a lot longer ago then than such a span

of time is regarded today), discussing the good ol'

days of the Biograph company or actors and actresses

he worked with, such as Mary Pickford (Donnell, Kingsley).

Curiously, in one of these issues where Walthall was

"remembering when," The Birth of a Nation was

voted "Most Popular Picture" ten years after its release.

In 1928, director Percy Knighten went so far as to name his

film starring Walthall The Little Colonel in what

a reviewer from an unknown clipping source claimed was

"a sad attempt to repeat Henry B. Walthall's success in

'The Birth of a Nation.'" This film no doubt is lost and

does not even appear in Walthall's filmography. Perhaps there

is a reason as the reviewer goes on to add that "Knighten is no

Griffith." Still, although many of Walthall's films during this

period were not received with enthusiasm and are largely forgotten

today, those who reviewed films like Light in the Window and

The Phantom in the House, usually discovered at least one positive

element: Walthall's performance. Comments such as "H. B. Walthall acts

very well. The others are good enough to pass" (review for The Phantom

in the House) or "bad script, but our old

friend Henry B. Wallthall registers neatly" (review for the Warner Brothers

Vitaphone short Retribution) were not uncommon. Walthall kept

climbing to reclaim his place among the top film actors. Not

a year went by without Walthall appearing in at least a few pictures.

A 1930 photo from an

unknown source has the following caption: "Today Henry

B. Walthall plays small roles in the talkies, forgotten

by the newer generation, But, to the older, there will never be a screen

actor so compelling, so romantic, so lovable. To him--the little

colonel of "The Birth of a Nation"--this page is dedicated." These

"small roles in the talkies" were the beginning of new found fame

for the "Little Colonel."

The Little Colonel: The Movie! Possibly the lowest

rung on the "mythical

ladder" in Poverty Row.

Viva Sound!

Many have read the stories of how a silent movie star's career went

south after the emergence of sound because his or her voice was not

suitable for the talkies. Usually, even in the case of John Gilbert,

such stories were myths. In Henry B. Walthall's case, however, the

opposite held true. His stage-trained voice, rich and clear, proved

perfect for authoritarian roles. Walthall often played fathers, uncles,

lawyers, professors, and, yes, those dreaded ministers. Like most

actors of the silent period, Walthall was skeptical about the new

talking pictures: "I think that silent acting is much more difficult

than the talking screen acting. You must put so much

into your face and gestures in the silent pictures. In

speaking lines, too, you drop all expression. Talking

pictures lack effectiveness for that reason" (Kingsley, pg. 103).

But the Talkies would "rediscover" Walthall and give

him the opportunity to do what few motion picture pioneers

achieved: find fame in both silents and sound.

That's no way to treat a little colonel!

Getting roughed up in

the early Talkie Speakeasy.

At the beginning of the Talkies, Walthall still usually

played bit roles, sometimes alongside legends before they

were legends, like John Wayne (Ride Him, Cowboy), Spencer Tracy

(Me and My Gal), and Clark Gable (Men in White).

He also made a brief, but memorable, appearance in D.W.

Griffith's first Talkie Abraham Lincoln.

In the minor production Police Court, Walthall enjoyed

one of his few leading roles of the Talkies. He incorporated

"expression" to his speaking role, especially in the death

scene. Walthall's character was pathetic; a former

star whose life has unraveled due to drink. He resorts

to dressing up like Lincoln and other Civil War figures

reciting speeches in a sleazy carnival--hardly the hero

he was in The Birth of a Nation. In Hollywood

terms, his time as a screen idol had past. Although

still extremely handsome and better looking than most

of the leading actors of the day, he had aged considerably

through the years. But heroes come in different packages,

and Walthall still had the ability to steal the show.

The first role in the talking pictures that gave Walthall

the recognition he deserved was as Francisco Madero

in Viva Villa! (1934). "The Little Colonel

Marches Back" declared an article celebrating Walthall

as the compassionate revolutionary leader.

"You cannot call it a comeback," the actor pointed out,

"because I have never really been away" (Rankin, pg. 70).

The role gave Walthall "a new lease on life," but his

greatest talking role was soon to come (Williams).

The film that catapulted Walthall completely

out of "Poverty Row" and placed him firmly on a

respectable platform in the acting field was Judge Priest.

Alongside Will Rogers, Walthall was the Reverend Ashby Brand

(yet another minister). His was a character role, but it

became far more than that. Judge Priest was the one

film of the sound era--not of the B-picture variety--that

gave Walthall the chance to steal the show at the

end. He seized this opportunity with relish. When the

closing credits ran, the viewer was left with a dominant

impression. The film was no longer about Will

Rogers' character, the character on trial, or Stepin

Fetchit's character; it was about Ashby Brand's moving

10-minute speech that tipped the scales in the case of

a former Confederate soldier. "I felt that the role had such

dramatic possibilities

that I expended every ounce of energy in making it

alive," Walthall explained, "I consider the part one of the

best I have ever played, regardless of length, and that

is the reason I became so enthusiastic in this interpretation"

(Williams). Walthall signed a contract with Fox within

24 hours of his courtroom scene. Praise from fans and Hollywood

people soon followed. "During the past few months my

fan mail has increased to very satisfactorily proportions,"

Walthall beamed, "My wife and daughter are as delighted as

I am" (Williams). The "Little Colonel" was the hero

again.

The hero again: Ashby Brand.

Several interesting films followed Judge Priest,

including A Tale of Two Cities with Ronald

Colman and Dante's Inferno with Spencer Tracy.

China Clipper in 1936 offered Walthall

another exciting opportunity. Walthall played airplane engineer Dad Brunn

who is pushed

to the limit by a man obsessed with starting a trans-Pacific mail route.

Brunn was a pivotal role and

Walthall received much air time during the first

half of the film. His character, however, suffered

a sudden demise. Walthall, himself, collapsed.

Ill from the beginning of the production, Walthall

soldiered through the scenes until it was obvious

that he could not finish the role. According to

the obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle, Walthall was working

at the Alameda

base of the Pan-American Airways under the constant care of a nurse.

When his condition worsened, Henry was brought back

to his

home to the San Fernando valley via boat. After a few days, physicians

had him transported to the Pottenger Sanitarium at Monrovia.

He failed to respond to

treatment and died at around 5:35 a.m. on Wednesday, June

17, 1936. Two accounts state that his wife and daughter did not arrive

in time to say their good-byes. The Los Angeles Times, however,

noted that his family visited him the day before. Approximately three weeks

passed

between leaving for home and his death. Ironically,

his illness forced Walthall to stop work before his

own character was to die in the film. The script was

altered, and Dad Brunn died off camera. This time his

illness was given a name, albeit ambiguous: intestinal influenza

exacerbated by

a nervous condition and an exhausting string of

uninterrupted film work.

Henry rehearsing his lines with wife Mary on the set of

China Clipper

The uniform still fits: Henry back in Confederate

grey

for Judge Priest with daughter Patricia. From the

Los Angeles Times obituary,

June 18, 1936, pg. 10.

Henry B. Walthall was many things: an actor, of course,

but a hunter, an avid reader, a dedicated Mason, a

southern gentleman and, above all, a good person.

His philosophy, according to brother Wales, was to

"be worthy of the regard of mankind" (Griggs, pg. 124).

He certainly was.

Upon hearing of 'Wally's' death, a shocked D.W.

Griffith made the following comments: "I don't know

whether you could call him a great actor, but this I am

certain--he had a great soul. It is given perhaps

to many to have great souls; it is given to only a few

to be able to express that soul to the entire world

by means of an expressive face and body, as Henry Walthall

did in The Birth of a Nation. Of course, the

world doesn't know and doesn't bother much about

that sort of thing, but he had a poet's imagination and

a beautiful face that could express the soul and

imagination he possessed. He was a gentleman, and, as

Hollywood puts it, 'a sweet guy.'" (Slide II, pg. 403).

We

are lucky to be able to see Walthall's "soul and

imagination" in some of his best roles like

The Birth of a Nation and Judge Priest,

which are still available for present and future generations

to enjoy.

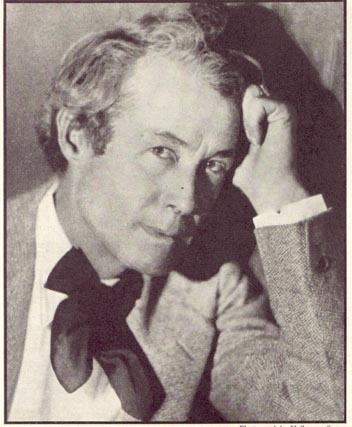

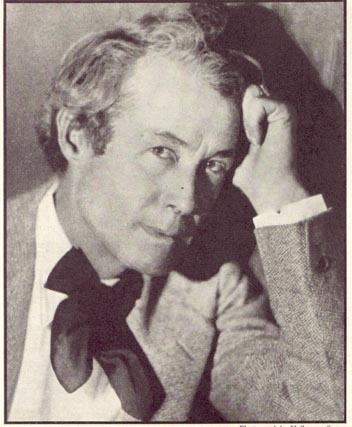

My favorite photo of Henry Walthall (sigh)

Please see the Bibliography

pages for details on the references used in this biography.

Free Counter